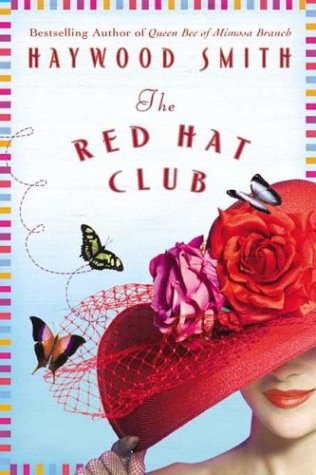

St. Martin’s Press

ISBN: 0-312-31693-3 (hardcover)

1-559-27967-2 (abridged cassette)

On Sale: October 5, 2004

Meet the Red Hat Club, the sassiest southerners since the Ya-Ya’s!

Meet Georgia, SuSu, Teeny, Diane, and Linda—five women who’ve been best friends through thirty years since high school. Sit in when they don their red hats and purple outfits to join Atlanta’s Ladies Who Lunch for a delicious monthly serving of racy jokes, iced tea and chicken salad, baskets of sweet rolls, the latest Buckhead gossip, and most of all—lively support and caring through the ups and downs of their lives.

When Diane discovers her banker husband has a condo (with mistress) that he bought with their retirement funds, the Red Hats swing into action and hang him with his own rope in a story that serves up laughter, friendship, revenge, high school memories, long-lost loves, a suburban dominatrix, and plenty of white wine and junk food. From the 1960s to the present, The Red Hat Club is a funny, unforgettable novel that shows the power women can find when they accept and support each other.

This novel is a work of fiction about a group of women who belong to a group like The Red Hat Society. It has not been authorized or endorsed by The Red Hat Society.

Buy Links

Excerpt

Swan Coach House. Wednesday, January 9, 2002. 11:00 A.M.

After a brief, nonproductive swing through the gift shop and gallery in search of some “thinking of you” trinket to brighten up my son Jack’s bachelor apartment or my daughter Callie’s dorm room, I went downstairs to the sunny main restaurant, cheered by the familiarity of its dark wood floors, chintz tablecloths, and padded walls bright with tastefully garish tulips. As usual, I was the first to arrive, still clinging to the illusion that punctuality was possible with the Red Hats despite more than three decades of evidence to the contrary.

“Table for five, please,” I said to the lone waitress, a plump, nondescript woman I didn’t recognize.

She didn’t blink at my red fedora, ancient sable car coat, and tailored dark purple pantsuit. The Red Hats were such a fixture here that our eccentricities had become part of the basic orientation for the staff. “Sorry, mah-dahm,” the waitress said in thick Slavic accents, “must wait for all here to be seated.” Clearly, she had no idea she was dealing with a Buckhead institution, one that was allowed to bend the Coach House’s ironclad edict. With the exception of private parties, mere mortals were never seated until everyone in their party had arrived. But owing to our longstanding presence, the Red Hats were the exception that proved the rule—provided we were discreet about it. Clearly, this new waitress hadn’t gotten the message.

I looked for her name badge, hoping the personal touch would thaw her out a little. She wasn’t wearing one, but I tried anyway. “My name is Georgia,” I said in my most approachable manner. “What’s yours?”

She arched an eyebrow in disdain. “You could not say it. Too hard.”

Serious attitude.

My master’s in Southern Bitch kicked in, smoothing my voice to honeyed ice. “What a lovely accent. Where are you from?”

“Romania,” the waitress answered with a defensive shrug.

Great. This was going to be a challenge for both of us.

“Please get the manager,” I said distinctly. “Tell her it’s the Red Hats.”

She scowled again.

I pointed to my red fedora. “Tell the manager that the Red Hats are here, and I want to be seated.”

She disappeared into the back, then returned with the apologetic manager du jour. “Sorry,” the young woman whose name tag identified her as JOSIE said in unctuous tones. “We were shorthanded, so we pressed Vashkenushka into service from the kitchen. I forgot to tell her about y’all. Please forgive us.” Despite the fact that we were the only ones in the cheery yellow foyer, she glanced about, her expression clouded with concern as she lowered her voice. “I really appreciate your continuing discretion about this arrangement, though. We’d have mutiny if the other customers found out.”

“Trust me,” I reassured her. “No one will ever hear it from us.” As if everybody who was anybody didn’t already know.

The manager’s brow eased. She motioned the waitress toward our regular banquette in the back corner near the kitchen door. “Seat the ladies in red hats as soon as they come in. Just this one group, no one else,” she instructed, “and treat them well.

They’re very special guests.”

“Yes, madam,” Miss Romania said, but her manner bristled with contempt as she led the way across brilliant slashes of winter sunshine that slanted through the white plantation shutters.

I sat down in the shady corner, but kept my coat on. The room was chilly, and I hadn’t been warm between November and April since 1989.

When our little group had first started meeting there—long before we were Red Hats—the waitresses had been Junior Leaguers working their required service placements. Back then, the bigger the diamond, the worse the waitress, and Atlanta’s well-to-do young matrons were seriously solitaired. The League had eventually hired paid staff, but the joke was on everybody for a while: the quality of service hadn’t improved for a long time. For the past decade, things had been much better, though still a little slow from the kitchen. But that was an accepted part of the mystique, along with the limited—but excellent—tearoom menu.

The Red Hats didn’t come for the service, anyway, or for the food. We came because the Coach House was an Atlanta institution, a link to our past with a great tea party quotient. I couldn’t count the bridal showers, baby showers, luncheons, and receptions we’d all attended there.

“To drink today?” the waitress asked with a decidedly aggressive note.

“I’ll have unsweetened tea, please,” I said. “No lemon.” I like iced tea, and I like lemon, but nowhere near each other.

“No coffee?” she challenged. “Isss cold today. Maybe hot tea?”

“No, thank you.” I suppressed a blip of irritation. She would learn. “Just plain iced tea, please, no lemon.” It’s a Southern thing, drinking iced tea at lunch even in the winter. Shrimp salad just doesn’t taste right with coffee. “And I’ll need lots of refills,” I said, smiling in an effort to lighten things up. “I’m a heavy drinker.”

Not a flicker of amusement crossed her broad face, prompting me to wonder if she didn’t understand, or if total lack of humor was one of the main requirements for working there, as I had long suspected.

“My friends will be here soon,” I told her. “We usually stay until closing. If you’ll keep our glasses filled, we’ll give you a big tip.” It was only fair, since she wouldn’t be able to turn the table.

“Big tip,” she seemed to understand, but she didn’t break a smile.

“I get your tea.”

A Romanian waitress at the Coach House. What next?

I still wasn’t accustomed to Atlanta’s being crowded with people from other countries.

Outwardly, I had met the onslaught with resolute enlightenment and Southern hospitality, but inwardly, a lingering part of me wanted to circle the wagons. Gone were the narrow social boundaries of my childhood—Crackers, Blacks, Catholics, and Jews, Mainlines and Pentecostals—erased by this new invasion that made unlikely allies of anybody who’d grown up here.

Maybe that was why we Red Hats clung even tighter to our little group as we grew older. It was the one solid connection to our past.

“George!” Diane called to me from across the room. She must have just had her hair colored, because her white roots were not in evidence below her red beret. She’d worn contacts since she was nine, but today the thick glasses I hadn’t seen in years contorted her attractive face into a peanut shape, reminding me of the momentous day we’d met so long ago.

Lord, I’d forgotten how blind she was without her contacts.

“I lost a lens and almost didn’t even come.” Even more flustered than usual, she muddled her way between the tables, poking through her enormous Vuitton shoulder bag as she bumped the chairs. “Dad-gum it. I put that paperback you loaned me in here somewhere, but now I can’t find it.”

Considering the shape the paperback would probably be in, I quickly reassured her, “Well, don’t worry if you can’t.” She was notorious for loving whatever she read nigh unto death—breaking the spines, slopping coffee on the pages, sometimes even baptizing them in the tub with her—so I only loaned her the ones I could live without.

I changed the subject. “Did you remember your joke? It’s your turn, you know.”

She flopped dramatically into the seat beside me. “Yes. But it’s getting harder and harder since Sally”—her good ole girl hairdresser—“had that stroke. She was my only source.”

“What about the new girl?”

Diane grimaced. “She weighs eighty-seven pounds, has black lips, piercings, and a fuchsia streak in her ‘bedhead’ hair. I don’t think she would know a joke if it bit her.”

I laughed. Diane was naturally a stitch, but she could not tell a proper joke for beans. “How many times have I told you?” I said, “You need to get e-mail. People send me jokes all the time. You should try it. Lee’s been dying to set it up for you.” Her only son, Lee, had graduated in business with a minor in Japanese from Harvard and a master’s from Wharton. Now he made big bucks consulting for a major Japanese company in Asia.

“Lee?” she scoffed. “From Tokyo?”

“He comes home every three months, and you know it.” We baby boomers might be dragged kicking and screaming into the Age of the Internet, but not our grown sons and daughters; they were all computer-savvy.

Diane, on the other hand, seemed to consider it a matter of honor to hold out. Very passive-aggressive, which was definitely her style. I loved her, but you had to be careful or she’d store up hurts, then bite you on the ankle when you least expected it.

“I swear,” I harped, “once you get on-line, you’ll love it. Instant gossip, honey.

And Lee would probably e-mail you every few days from Tokyo, instead of just calling once a month.”

“Right. And what about spam and viruses and upgrades and expense?” She adjusted her thick glasses.

I stifled the urge to laugh.

She peered at me earnestly from the depths of distortion. “I haven’t got time or energy for one more thing in my life. But since you’re so hot about the Internet, why don’t you just find me some jokes next time it’s my turn?”

“No. That defeats the purpose.”

Diane straightened the rich purple-and-red paisley of her challis skirt. “I thought the purpose of bringing a joke was for us to laugh,” she grumped.

“It is. But it’s also important for us to have to find the joke,” I reminded her. “Finding the joke requires positive personal interaction outside the group. It’s good for you. For all of us.”

“Lord.” Flat-mouthed, she sagged. “Like I said, I have enough to do without having to prod people for jokes.”

Game called on account of pain.

We both knew the secret sorrow she was talking about, but Sacred Red Hat Tradition Five (Mind your own business) kept me from prodding. If she ever decided to talk about it, she would. Frankly, if John had done to me what Harold was doing to her—after she’d put him through law school and remodeled their houses and been the perfect corporate wife for a quarter of a century—I’d have jumped off the top of Stone Mountain long since.

But then, I was the only one of us who hadn’t finished college and worked. I’d met John my junior year and taken the June Cleaver track.

Diane deflected the pregnant silence that had fallen between us by scanning the Ladies Who Lunch now filling the room.

“Where’s our waitress? Are you sure we have one?” she asked, reminding both of us of the long-ago meeting when we’d finally realized that nobody wanted to wait on us because they couldn’t turn the table. We’d triple-tipped ever since, and a good time was had by all.

I wasn’t so sure about today, though; Miss Romania had a chip the size of Bucharest on her shoulder. “I don’t see her. She’s new—Romanian, doesn’t speak much English. She took my drink order and promptly disappeared completely.”

Diane opened her napkin, then snagged another waitress on her way to the kitchen. “Excuse me, miss. Could you get our server, please? We need drinks and muffins and rolls and lots of plain butter.”

We didn’t need the rolls and butter, of course, but some of us wanted them.

“Right away, ma’am.”

I looked past her to the entry, saw a small red pillbox hat bobbing through the waiting patrons, and waved. “Oh, good. There’s Teeny.”

Teeny nodded in acknowledgment, doing her best not to attract attention in her tasteful black reefer coat and impeccable purple wool sheath as she skirted the room in our direction. When she reached us, she slipped gracefully into a chair, her blue eyes less shadowed than they’d been in a long time.

“M-wah, m-wah.” Hats grazing, Diane did that fake Euro kissy thing on either side of Teeny’s delicate features. “Look at you, Teeny girl, gorgeous as Audrey Hepburn in that new dress. I swear, you don’t look a day over twenty in that outfit.”

As always, Teeny responded to the compliment with awkward pleasure. “Thanks.” She shrugged off her coat, revealing tapered sleeves in a rich bouclé wool. “I made it.”

“You are joking.” I reassessed the simple, elegant creation. The cut was sophisticated and beautifully tailored. “I’m gabberflasted. It looks like you paid a fortune for it.” Teeny hadn’t sewn since our boys were in T-ball, but her rotten, rich husband kept her on such a short leash financially that she might have been forced to take it up again. The possibility annoyed the poo out of me, but no way would I let on. Teeny was allergic to conflict of any kind. “That tailoring. I can’t believe you actually made it.”

Teeny’s eyes glowed as she looked down and to the right. “Thanks.”

Diane gave her a sideways hug. “Worthy of Old Miz Boatwright’s Home Ec class.”

“Miz Boatwright,” I mused. “Now there’s a blast from the past. How in this world did you remember her? You didn’t even go to Northside.”

“SuSu and Linda bitched about her enough.” Diane mimicked Linda’s dead-on imitation of the woman we had tortured for trying to teach us to cook and sew. “No spiders, ladies. Tie and trim those loose threads, or it’s ten points off for every one of ’em.”

Teeny giggled behind her hand, prompting me to wonder yet again if she ever let loose and laughed aloud like she used to. Our monthly jokes were no way to tell. She never “got” them. And she was even worse than Diane at telling them.

“Miz Boatwright,” I repeated, nostalgic. “Ruling duenna of Northside’s domestic arts.” Her image sprang vividly from three decades ago, surrounded by cutting tables, arcane kitchen appliances, and sewing kits in the Home Ec lab. I could still remember the faint underscent of sewing machine oil mingled with the aroma of the muffins she baked every morning for her friends on the staff. “A blast from the past,” I repeated.

“Who’s a blast from the past?” Linda approached from behind a group settling at the table beside us. Her wide face was framed by soft, shiny silver curls that only she, among us, had the courage to wear. She looked ten years older than we did, but didn’t care, secure in her doting husband’s love. Her red knit waif-hat and bulky purple sweater earned a few curious glances before she plunked into her usual chair.

“Miz Boatwright in Home Ec,” I informed her. “Diane actually remembered her name.”

“Ah,” Linda nodded. “The poor soul who tried unsuccessfully to make proper homemakers of us.” She looked to Diane. “Thank your lucky stars you didn’t have to suffer such nonsense at Westminster.”

“I’m sure they assumed you’d hire all that out,” I said without malice. It was true.

Linda looked at me. “Miz Boatwright succeeded with you, George. You can cook like Julia Child and sew almost as well as Teeny.”

“My sewing days are long gone. The last thing I made was a Nehru jacket for John.” Then a sobering thought struck me.

“Oh, gross.

Do you realize that when we were in her class, Miz Boatwright was probably younger than we are now?”

Linda groaned. “Thanks a lot for that cheerful little observation.”

Teeny jumped in with a prim, “Perhaps you’d like to follow it up by counting crow’s feet. If so, I suggest you start in the mirror.”

“Teeny!” I perked up, hoping she’d intended the zinger. But she simply blinked back at me with her usual wide-eyed innocence. Teeny didn’t have a hostile bone in her body; she just said whatever she thought without considering how it might sound.

Uncomfortable at the mere hint of conflict between Teeny and me, Diane invoked the first of our Sacred Red Hat Traditions:

“Do over.”

Tradition One (Do over): Any one of us, at any time, can simply ask for a fresh start and get it. Change of subject, change of attitude—no matter how bad we might have screwed things up (in which case, immediate apologies are in order).

Diane peered in her best ex-schoolteacher manner at both of us.

“I’m in no mood to be reminded of my middle-aged shortcomings, even by Teeny.”

“Oh, for cryin’ out loud, Di,” Linda chimed in, “Teeny didn’t mean anything by it.” She never did.

Frankly, any one of us would have been delighted if she had. She hadn’t stuck up for herself since 1974, the one and only time. (More about that later.) We all longed to see her stand up to that sorry, good-looking, good-for-nothing husband of hers. But Teeny would steadfastly keep up appearances, hanging quietly on her discreet, tasteful martyr’s cross until the day she died, and we’d love her anyway.

“So.” Linda steered to a topic we could all safely complain about. “Where’s the waitress? Don’t tell me you’ve scared her off already, George.”

Did I mention that George is my nickname? It’s short for Georgia, but not my native state. That would be too redneck. My mama was very artistic and forward-thinking, so she’d named me after the infamously liberated artist Georgia O’Keefe, a fact that has always given me a clandestine sense of scandalous satisfaction. But only the Red Hats and my husband are allowed to call me George.

Miss Romania finally appeared with my tea—with lemon despite my request otherwise, dad-gum it—and a small basket of bread with strawberry butter balls.

I removed the wedge from the side of my glass, then wiped the rim with my napkin, but the damage had been done. That first glass would taste faintly of disinfectant to me, even with plenty of Sweet ’N’ Low.

Typically straightforward, Linda took charge of the bread basket and assessed its skimpy contents. “I’m afraid we’re going to need lots more than this.”

When the waitress frowned, clearly confused, Linda clarified, pointing to the tiny muffins and fat rolls. “More bread, please. Now. And much plain butter. Plain butter.”

Still scowling, Miss Romania disappeared—without taking the drink orders.

Linda helped herself to a muffin. “Yum. Poppy seed.”

“Well, keep ’em down there by you, ” I grumbled. “Don’t tempt me. I have to save my calories for the main course.”

“Tradition Twelve,” Linda invoked. (No mention of weight or diets.) Passing the rolls to Teeny—whose metabolism, unlike the rest of ours, kept her rail thin no matter what—she promptly shattered the same tradition. And Tradition Five. “I’m tellin’ you, George, as long as you walk at least four times a week and give up on trying to look thirty again, fat’s like dust: it reaches maximum thickness pretty quickly. Then you can eat whatever you want within reason without gaining any more.”

Easy for her to say. Her devoted little urologist husband was as

barrel-bodied as she was. But my husband had grown increasingly thinner and more distant in recent years, working out and working late with driven compulsion. I dared not risk letting myself go.

Of course, I was still operating then under the illusion that if you “did it right,” your marriage would be safe from the plague of infidelity that had wiped out most couples we knew. It had started slowly with our parents, then spread like some immoral Ebola through our own generation, with Bill Clinton as its poster boy.

At the sound of a familiar smoker’s cough over the polite din of female conversation, we all turned to see SuSu hurrying in, her freckled face over tanned and her once-red hair a strangely greenish hue. She never wore a hat, red or otherwise; flatly refused.

She could have used one, though. One look at her hair, and I didn’t have to see the others’ reactions. I knew that another of our sacred traditions was on its way as soon as she got settled in.

“Hey, y’all,” she said in her husky smoker’s voice as she shucked her jacket, revealing the khakis, sweater, and white shirt that were her flight uniform. “I’ve gotta leave early to work the six o’clock to Houston, so let’s get this show on the road.”

Essence of SuSu: arrive at least half an hour late, then cause a scene trying to hustle everybody up.

None of us wasted any emotional energy being annoyed by it anymore. We did, however, compensate by teasing her about being the world’s oldest stewardess.

“You manage to get to the airport on time,” Linda chastened. “So we know you can teach an old dog new tricks. How ’bout spendin’ some of that newfound punctuality on your best friends for a change? Don’t we deserve it?”

“Punctuality is precious,” SuSu shot back. “What little I can muster up, I have to save for matters involving money.”

Still, I kept hoping she might eventually apply some of it to her social engagements.

“Where’s the waitress?” SuSu asked with a familiar, dangerous glint in her eye, scanning the menu as if she actually might order something besides her usual. “I’ve gotta be out of here by two.”

She closed her menu decisively, rose, and headed for the foyer. “I’m gonna tell the manager we need some service.”

“Our poor waitress,” Teeny murmured, her gentle soul always pained by confrontation. “She doesn’t seem to understand much English.

I don’t think it was very wise of them to assign her to us.”

Linda cackled. “God, no. We’re something you work up to.”

“Yeah,” I chimed in, “like waitress boot camp: a shared ordeal that bonds the staff together.”

Diane let out her throaty chuckle. “Somebody gets to be the Princess and the Pea. It might as well be us.”

“Princess? Hah,” I said with more than a hint of bitterness.

Princesses, indeed. We had all had our tantalizing taste of happily ever after, but only Linda’s had lasted. The rest of us were living in denial or running scared. SuSu had lost everything, forced to support herself after two decades of wife-and-mothering.

“Oh, dear.” Teeny peered toward Josie, who, standing beside a haughty SuSu, was searching the room for our invisible server. “I hope SuSu doesn’t get snippy this time.”

There was a heartbeat of silence; then the four of us—even Teeny—burst out laughing, loud enough to draw stares and muffle the herd-of-birds roar in the room.

Of course SuSu would get snippy. She always did, but we loved her anyway, just as we overlooked her chain smoking (thank God the restaurant was smoke-free), her drinking, her stubbornly disastrous taste in men, and her persistent failure to wake up and smell the coffee.

Diane motioned her back over. Before SuSu reached the table, our favorite waitress, Maria, emerged from the kitchen with warm rolls, plain butter, and her pad. “Sorry about the hang-up, ladies. Seems Vashkenushka just up and left without telling anybody.”

“Oh, gosh.” Teeny grimaced, quick to take responsibility and drag us along with her. “Now see what we did. We ran that poor woman off.”

“Well, good riddance if you did,” Maria said matter-of-factly. “The devil owed this place a debt, and he paid it with that woman.” She lowered her voice conspiratorially. “The manager only put her out front because the cook threatened to quit if she didn’t get her out of the kitchen.” She poised her pen. “How about drinks? Water for everybody, plus the usual?”

Linda considered, buttering a roll. “Could you make us some more of that hot lemonade you did the last time, Maria? It was so-o-o good.”

“Certainly. How about a couple of pots for the table?”

The room was still cool, and the hot lemonade sounded wonderful. “Good with me.”

The others nodded.

“All right, then.” She knew without being asked to take our orders right away. “The soup of the day is clam chowder, and the fish is pan-seared tilapia with a lemon-butter sauce.” She patiently endured the cosmic compulsion that causes Ladies Who Lunch to complain about the delay while waiting to order, then dither like they’ve never even seen a menu when the waitress finally arrives with pen in hand.

I won’t even discuss the thing about splitting checks and the havoc wreaked by to-the-penny purists. In the interest of time and global tranquillity, Maria also knew without being asked to do separate checks.

After allowing a decent interval for consideration, I went first, as usual. “I’ll have the shrimp salad plate, please.”

Maria scribbled away, flipped the page, then waited through the lengthy passive-aggressive pause of indecision that followed.

I kept myself from getting annoyed at the others’ dithering by checking for familiar faces across the room, but found none. An office luncheon of twelve, six Talbotsy, white-haired quads, lots of upscale duos, and a corner table with three women in tennis sweats, which was so not done these days.

Not a soul I knew. It just wasn’t our town anymore.

Finally, Diane got things rolling again by ordering her usual. “I’ll have the Favorite, no pineapple, please.”

“Same here,” Teeny followed on cue. “But pineapple’s okay for mine.”

Linda muttered over the hot entrées, then ordered what she always did. “I’ll have the French onion soup and chicken salad croissant.”

“Very good.” Maria removed their menus, waiting for SuSu to make up her mind.

“A glass of Chablis and the combination plate,” SuSu finally declared. “But bring me regular coffee, too, please.” She turned to us. “I need the caffeine. The flight goes on to Arizona, then Salt Lake City, so it’ll be morning before we make the layover.”

Coming from SuSu’s mouth, the term layover was a double entendre of galactic proportions, but the four of us managed to keep straight faces.

We waited until Maria was gone before we all leaned in toward SuSu and whispered, “MO! Big-time.”

Red Hat Sacred Tradition Two: Anybody can call a makeover (MO) when it’s warranted.

“What is with that hair color? Shades of senior green,” I said sotto voce, referring to the summer I’d worked as a lifeguard in high school and ended up with olive drab instead of bleached blond hair.

“The color’s not nearly as awful as George’s was that time,” Teeny was quick to soothe, “but it definitely has a cast of that same green.”

“You didn’t resort to drugstore hair color, did you?” Linda asked, aghast. “’Cause that’s what happened to my cousin’s friend. The salon color interacted with the cheap stuff, and she went bald within a week. Had to wear an Eva Gabor wig for more than six months while her hair grew back out.” Sounded like an urban myth to me, but Linda clearly believed it.

“Of course I didn’t use that junk,” SuSu said, indignant to be accused of one of the most alarming signs of impending poverty or personal neglect in a Buckhead girl. “Charles still does my color, just like always.” She clearly wasn’t taking the MO in the spirit of sisterhood. “Granted, I’m a little late getting to him this month. I had to cover for a flight on my regular appointment day. But I haven’t sunk to shampoo-in.”

Diane peered at her uncovered coiffure. “Kinda that pool-green color we got as kids.”

“Pool.” SuSu’s eyes sharpened as the truth sank in. “Shit.”

“Ha. Mystery solved.” I drove the point home. “Those layovers in Cancún and Arizona and New Mexico. Pool hair.”

At least SuSu had the good grace to look sheepish. “I’ve been swimming laps.” She pulled a thick shock of her stylish bob toward the front for a closer look. “Double shit. It is green.” She flicked it back into place. “Oh, well. Charles’ll fix it next week.”

The rest of us exchanged glances.

“Speaking of Charles, Suse,” Diane ventured, “maybe this might be a good time to try somebody else. He hasn’t done you any favors for the last few months.”

SuSu scanned our faces for confirmation and got it. “Why didn’t you say something sooner?”

Ever the peacemaker, Teeny leaned forward, sympathetic. “It just happened sort of gradually. Today’s the first time it’s rated an MO.”

“Okay. I’ll consider it, but next month. I don’t have time to go hunting.”

“Try Joanna, at Athena on Buckhead Avenue,” three of us said in unison.

“You can have my appointment next Tuesday,” Linda volunteered. “You’ll love her, and she can fit me in anytime.”

“Okay. Enough. I’ll go.” Uncomfortable, SuSu glanced toward the kitchen. “Where’s my wine?” She turned back. “Enough about me. I call a do over. Who’s got the joke?”

Diane raised her hand. “Me, but remember, joke-telling is not my forte.”

“We live in hope, Di,” Linda said as always. “Go for it.”

She pulled out a paper from her purse and unfolded it to reveal her loopy, inflated handwriting. “A Buckhead housewife and her husband were having an argument about sex,” she read, dropping her voice on the last. “‘You never tell me when you’re having an orgasm!’ the guy yelled.

“ ‘How can I?’ she yelled back. ‘You’re never here!’ ”

Linda and SuSu laughed. I’d heard it ages ago, but laughed anyway.

“Good one,” SuSu ruled.

“I second that.” Linda.

Teeny smiled politely, a quizzical expression on her face. We’d long ago given up on trying to explain the jokes to her. We loved her as much because of her naïveté as in spite of it.

Suddenly Diane looked as if she might burst into tears. “Okay, now that that’s out of the way,” she said, leaning in to keep anyone beyond the table from hearing, “I’ve got major trouble, and I need y’all to help me.”

That got our attention, pronto. Spring-loaded with concern, four red hats and one green head huddled up as she reached into her pocket and produced a tidy little note that she smoothed out next to the bud vase where all of us could see it.

“Buy sheets—310 thread count. Paint the kitchen,” it said in a precise male hand.

“I found that in the pocket of Harold’s suit last night.”

“So?” Linda asked.

“We don’t need any sheets,” Diane growled in a tone I’d never heard her use before. “And he sure as hell isn’t painting any kitchens at my house!”

At last. She’d finally acknowledged the truth that we had long since known. The question was, what was she going to do about it?

My mind swirled with possibilities. I was great at analyzing my friends’ problems—almost as great as I was at denying my own.

Reviews

From Library Journal:

“By turns humorous and poignant, this is a novel with characters so real that even non-Southerners will find them familiar.”

From Booklist:

“Smith’s celebration of comradeship is a loving tribute to those lifelong relationships that may defy logic but are destined to outlive many other associations. A joyous, joyful ode to the older woman.”

From Romantic Times Book Review:

“Told in first person by one of the friends, this story is a wonderful journey, as older women discover life can continue to be new and challenging after middle age…This book is not only fun to read but, for some, may even be a learning experience.”